There is the common hypothetical conversation that gets circulated in the business world around training that summarizes the key concerns about providing high quality training to your team members.

The CFO says something along the lines of, “What if we train them and they leave?”

The CEO then, being wise as she is, says, “What if we don’t, and they stay?”

There is a natural tension being expressed here, and I thought it would be an interesting exercise to explore it from a microeconomics perspective. One path of consideration is presenting training as a non-monetary benefit to candidates, which can serve as a recruiting and retention tool in its own right. That is a very relevant perspective, and it warrants its own analysis. However, my focus here is how a company should behave if it views training as an investment in human capital.

My ultimate conclusion was that it would be most sensible to provide training with a vesting mechanic, so that if someone who accepts training dollars and they leave the company voluntarily within a certain time frame, they would be obligated to pay all or some portion of that money back. It is a practice at companies I have worked at in the past, and it seems sensible based on the analysis below.

Firms must decide on how to balance inputs in order to reach a certain optimal outcome. One of said inputs would be human capital. Human capital is accumulated through investment, not unlike the acquisition of physical capital. However, there are certain risks involved in the investment of human capital that one does not incur with physical capital, as physical capital can usually be sold to retrieve the investment minus depreciation. On the other hand, the retention of human capital investment is contingent on the continuous cooperation of each individual laborer and the investment can never be returned directly into liquid value.

The fundamental mechanic of capital investment requires the investor to sacrifice present resources in order for a larger payoff in the future. The decision must be made to put off resources today in order to gain some greater utility in the future. One way to establish a framework for decision making in this case would be the present discounted value approach to investment decisions (Nicholson 2005, p. 510).

PDV= R1/(1+r) + R2/(1/+r)2 + … + Rn/(1+r)n (Equation 1)

In the case of physical capital investment, the model allows one to discern the present discounted value of a projected revenue stream produced by the capital in question for some expected number of years, n. If the present discounted value of said revenue stream is greater than the present price, p, of making such an investment, then the firm should make the investment. On the other hand if the present discounted value of the stream of revenue from the capital in question is lesser in value in comparison with the price of investment.

Now, this same framework for decision making regarding physical capital can be applied to human capital as well. For example, a student who is facing the decision of whether or not to attend college can calculate their expected lifetime income with and without a college degree then compare the present discounted value. If the difference is greater than the price of tuition as well as the forgone income of working during attendance, then it is worthwhile to invest in the degree.

However, there is a complication for employers investing in the general training of their employees. In the case of physical capital, there is a projected number of years that the capital will last, n. For human capital, there is a risk factor of a laborer leaving the firm at some point after the investment is made. Thus, there is some uncertainty regarding the value of n, which leads to the inability to calculate the present discounted value with any decisiveness.

In order to understand this risk more specifically, one can examine a simple behavioral game in reference to the decisions being made by laborer and firm.

| Employer | |||

|

|

Invest | Do not invest | |

|

Employee |

Move |

3, -1 |

2, 0 |

| Stay | 3, 2 |

2, 1 |

|

(Figure 1)

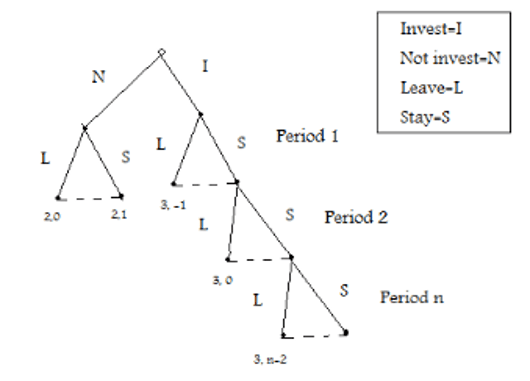

Figure 1 depicts a scenario in which the employee would be indifferent to staying or leaving for another firm regardless of the choice of the firm to invest or not invest in said employee. Thus, there is an element of uncertainty for the employer to invest, which indicates there is no strictly dominant strategy for the firm. One could convert this static normal form game into a dynamic extensive form game with n periods to reflect the Present Discounted Value model in Equation 1.

(Figure 2)

(Figure 2)

Figure 2 shows a dynamic model where the employee chooses to stay or leave at the beginning of each period. The firm does not know if or when the employee will choose to leave the firm, shown as imperfect information. This imperfect information ends with the same result as the static model. There is no strictly dominant strategy for the firm unless one of three elements change: either (Possibility A) the employer’s cost of training must be offset, (Possibility B) the employer can guarantee superior utility to employees that stay with the firm, or (Possibility C) there must be some guarantee that the employee will stay for some minimum periods[1], n, in order to ensure that the present discounted value of the revenue stream from the employee in question will be greater than the cost of the initial investment.

In Figure 2, the employer incurs all costs of investments in human capital. One derivative of Possibility A would include the sharing of costs for investment in human capital between the employee and the firm up to the entirety of costs being accounted for by the employee. This concept is explored by Gary S. Becker in Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education. Becker contends that employees receiving general training would be willing to pay the costs as the increase to their marginal productivity would be transferable to any other firm. In his own words, “employees would pay for general training by receiving wages below their current (opportunity) productivity” (Becker 1975, p. 21).

Another derivative of Possibility A would be the government subsidizing of general training to offset the costs to firms. The rationale for subsidizing general training lies in the fact that, despite Becker’s assertion that employee’s should be financing their own general training, it would appear firms are incurring costs as well “since jobs with large initial general training requirements do not have lower starting wages” (Carlstrom and Rollow 1998, p. 3). Carlstrom and Rollow go on to state the possibility that in this case, “the amount of training provided by firms-particularly high-turnover ones-may be suboptimal” (Carlstrom and Rollow 1998, p. 3). Going back to Figure 1, a high turnover firm would be characterized by one in which a large percentage of employees choose to move instead of staying at the firm. The firm would then retain only a small percentage of their investment in the remaining employees and is not incentivized to invest in general training. Granted, there is some uncertainty regarding what can be classified as specific training, the value of which would be necessarily retained by the firm, and general training, the value of which is retained by the worker regardless of employer. This uncertainty makes it difficult to specifically calculate and justify a precise subsidy that would ensure some socially optimal quantity of general training.

Possibility B explores a scenario where the firm acknowledges that it will take on the full cost of general training for the employee, but is able to ensure that it will reap the benefits of the training by focusing on the retention of the employee. This possibility is rather simple under a system of perfect information as the firm simply needs to ensure that the alternative wages for the employee are less than the wages at the firm providing the training all other considerations held constant. The complication arises when the cost of retention plus the cost of training exceeds the returns from investment. An additional complication arises under imperfect information where the firm investing does not know the alternative wages that the employee may earn on the market. Thus, Possibility B is a rather limited solution.

Possibility C is one of the more straightforward solutions to the issue of uncertainty regarding the length of time the employee receiving training will stay at the firm. The firm can simply provide the general training contingent on a guarantee that the employee will remain with the firm for the minimum number of periods, n, required to reap a profitable return. There are a number of contractual arrangements in the market that can be highlighted as examples such as general training provided by the military that requires some minimum number years of service in return. However, there may be some legal limitations regarding contract length dependent on the industry in question.

Ultimately, firms cannot outright provide an optimal amount of general training for laborers due to the uncertainty as to whether or not trainees will transfer the benefits of the general training to another firm. The provision of said training is reliant primarily on the employees themselves to support the costs and choose precisely how much general training they desire. There are alternatives such as government support. Another alternative would be a contractual arrangement that can guarantee that the firm providing the training will reap the benefits as the employee would be obligated to stay at the firm for some minimum amount of time as determined by the present discounted value of future revenue from said employee. Further exploration into the brief overview of the three possibilities presented would be beneficial.

List of References

Becker, Gary S. 1975. Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special

Reference to Education, 2nd ed. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Carlstrom, Charles T. and Rollow, Christy D. 1998. Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland.

Economic Commentary (March).

Osborne, Martin J. 2004. An introduction to Game Theory. Oxford University Press, New York.

Nicholson, Walter. 2005. Microeconomic Theory: Basic Principles and Extensions. Thomson

South-Western.

[1] In the case of figure 3, the employee only needs to be guaranteed as staying for one period in order for the firm’s dominant strategy to be to invest. However, this is an arbitrary example that is simply constructed to show the fundamental concepts behind said investment decision and the discrete values listed have no actual bearing on empirical data.